This was going to be the topic of one of the presentations I got accepted at FOSDEM 2025. Unfortunately, a nasty flu got the best of me, so I had to cancel my attendance… As such, I decided to try and summarize the main points of the presentation I wanted to give in a more structured (and possibly too long?) post instead.

Motivation

I love orchestral music. And when I say it, I really mean it! I love classical music (especially symphonic), I love cinematic soundtracks, I love the sound of an orchestra, and I particularly love it whenever orchestras somehow meet the world of rock’n’roll (or something heavier than that!), in a mix that shouldn’t work and instead often does.

There are many examples of that: Deep Purple famously recorded a live album with the Royal Philarmonic Orchestra, Malmsteen wrote a full classical concert for electric guitar and orchestra, and Skálmöld played their classics with the Iceland Symphony Orchestra in what is probably my favourite metal/orchestra mix of all time, but there are a ton of bands that incorporated orchestral elements in their studio albums too (e.g., Rhapsody of Fire, Dimmu Borgir, Septicflesh, Nightwish, etc.).

But, as I said, I really love purely symphonic music as well: Tchaikovsky is my favourite composer of all times, for instance. As such, I’ve always had a fascination for orchestral music in general, and I’ve always wanted to write a symphony, which at a certain point brought me to the question: how easy would it be to score an orchestral track myself? And when it’s written, how easy would it be to have it played in a way that’s more or less “believable”?

Ages ago, back in my Windows days (so maybe 20-25 years ago), I remember experimenting with a copy of a software called Sibelius. In fact, while the other software I was using to score MIDI parts (Cakewalk) was serviceable, its orchestral rendering qualities were pretty much non-existant, while Sibelius felt like you could actually have an orchestra in your pocket. I only used it for a short time, though, and then I hit a long pause on my music composition/production days, which I only got back to more or less recently, about 5-6 year ago.

In the meanwhile, a lot had changed. I had switched to Linux for good, and had embraced a completely different ecosystem for music, thanks to the JACK Audio Connection Kit (and now Pipewire).

Part 2. (of what?)

I did talk a bit about the FOSS music ecosystem on Linux in a previous presentation at FOSDEM, two years ago. More precisely, I had prepared a talk called “Become a rockstar using FOSS! (or at least use FOSS to write and share music for fun)”. Of course, as the image below shows, it was very much a clickbait title…

Nevertheless, drawing from my experiences, I tried to give a more or less comprehensive overview, in the little time I had, on the FOSS music ecosystem on Linux, starting from the unique approach JACK/Pipewire provided compared to other systems, and then explaining the basics of connecting heterogenous applications with each other for the purpose of creating more or less complex media flows. It covered, for instance, how to capture your guitar, connect it to a virtual amp on your laptop, and then connect the output of that to something else (e.g., a DAW); or how to connect MIDI signals to sequencers or synthetizers, or both at the same time, to end up with audio signals that could then be the object of further processing.

It was a very high level talk, but it provided, I think, a decent introduction to a world so few seem to unfortunately be aware of. In fact, while I love FOSDEM, there’s basically no trace of anything related to music production: if there ever were devrooms devoted to that in the past, there certainly are none now. As a consequence, many people interested in music and in love with open source, often don’t even know what their laptop/computer is capable of with the right software.

This other presentation was indeed meant to be Part 2. of the “rockstar” presentation from two years ago, with a much stronger focus on virtual orchestration than on how to handle real instruments. So let’s dig into that!

What is Virtual Orchestration?

In a nutshell, Virtual Orchestration is basically the process of creating orchestral sounds by using virtual instruments. In fact, while it’s theoretically possibly to bring a score you write to a real orchestra to have it played, let’s face it, that’s never going to happen for the vast majority of us… There are a lot of people in an orchestra, all typically (and hopefully!) paid to play there. That means that, for most of us, simulating such an orchestra is pretty much the only way of bringing our inspiration to life: it simply is much easier (and cheaper) to write a score and have your computer perform it somehow.

Of course, that’s easier said than done. A real orchestra can host up to 100 musicians or more: that’s even more instruments than that, considering that some musicians (e.g., in the percussions section) are often responsible for more than one instrument, within the context of an orchestral piece. If you consider how many instruments there are, and how different they are from each other, you can imagine the huge variety in tone and expressivity that an orchestra can have when you jump from one section to another, or even from one instrument to another.

The sheer number of instruments at play, and their unique characteristics, are indeed a key aspect of why virtual orchestration is important to get right. In fact, there are different ways of solving the problem, but the main objective remains the same: trying to get whatever you do to sound more or less realistic, eventually. The quality of the audio samples of course matters (that’s why some of the most popular libraries are so awfully expensive), but it’s also sometimes not enough. What I’ve found out, for instance (and it may be an obvious observation; it wasn’t to me initially), is that a proper arrangement can help make the whole thing sound more realistic even with poorer samples (more on that in a minute). But another thing that helps is also pure “smoke and mirrors”, and/or just plain misdirection! Maybe your oboe samples sucks, or the clarinet sounds super fake: but when put in the context of a more complex piece, where other sections contribute to the mix, it may not matter that much after all. Sometimes, something that kinda sounds like an oboe may be enough, in the right context. That’s even more true when bringing an orchestra to a rock track, for instance: when “fighting” for audio space with drums, bass, guitars and maybe keyboards, the shortcomings of your orchestral samples may be less evident, and less important, and still be able to provide the proper impact you need in your track.

What instruments are there in an orchestra?

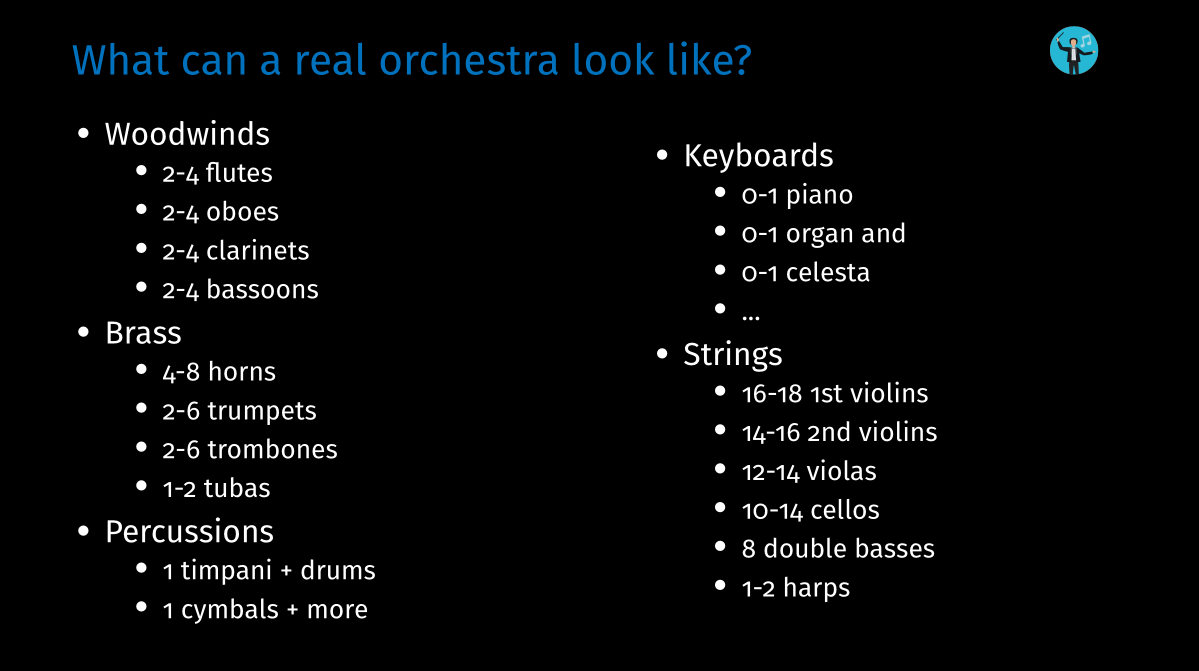

There’s not a single answer to that question, since it very much depends on the music piece: different symphonic pieces, for instances, can have different requirements, and the structure of an orchestra itself changed a lot over the centuries. A typical symphony orchestra you can find now will be quite different than the one you may have met in the 19th century.

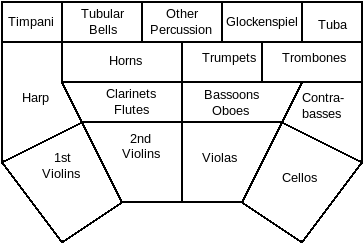

That said, we can try and categorize them into different sections. Without considering this as normative (there are excellent books and resources that go in more detail on that), you can typically, borrowing a slide from my presentation, split an orchestra this way.

As we pointed out already, that’s a lot of people, and a lot of instruments! The fact that the number of instruments is not fixed is a call back to what I was saying before, that is that how many there are really depends on what the composer wanted for the piece to play. Besides, some instruments may not even be there: you won’t see a piano in a symphony, for instance, but it will definitely be there in a piano concerto. And the list above doesn’t even mention choirs: that could increase the size of an orchestra considerably!

In a nutshell, though, what’s important to understand is that we can consider an orchestra as composed of different sections, each containing instruments that somehow “belong” together. And for every instrument, we can often also cluster them together in groups: this means, for instance, that we don’t really need 20 different violins, but we probably only need a single instrument that represents 20 violins playing together. The same, with some caveats, can be said for most instruments in that list: sometimes you’ll need a solo flute, some other times all flutes will play the same thing. These are just things to know and take into account, as most virtual orchestration solutions provide ways to address both use cases.

But before we get to how you can actually score and render orchestral music, an important point…

Don’t skip some actual homework…

Don’t assume that, just because virtual orchestration exists, it will magically solve all your problems! Yes, you’ll find good samples, and yes, there will be ways to address different scenarios, but a computer can’t do all for you. What I’ve found out is that it can help, tremendously, to know something about how real orchestras work: that can play a huge role when you write and arrange your piece, especially to make everything sound more realistic. All the orchestral music we love sounds like that because it’s actually a combination of parts, rather than a single “orchestra” instrument: that’s also true for the infamous “Hans Zimmer Brass”!

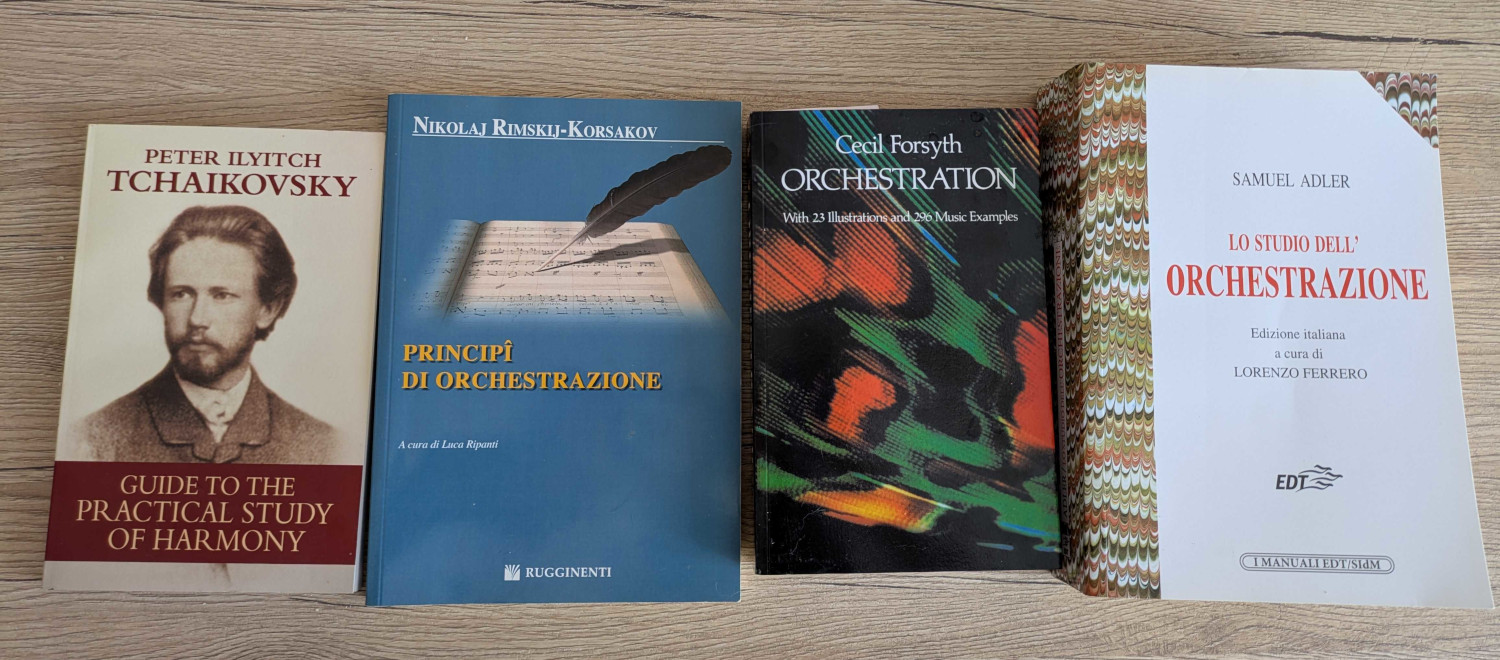

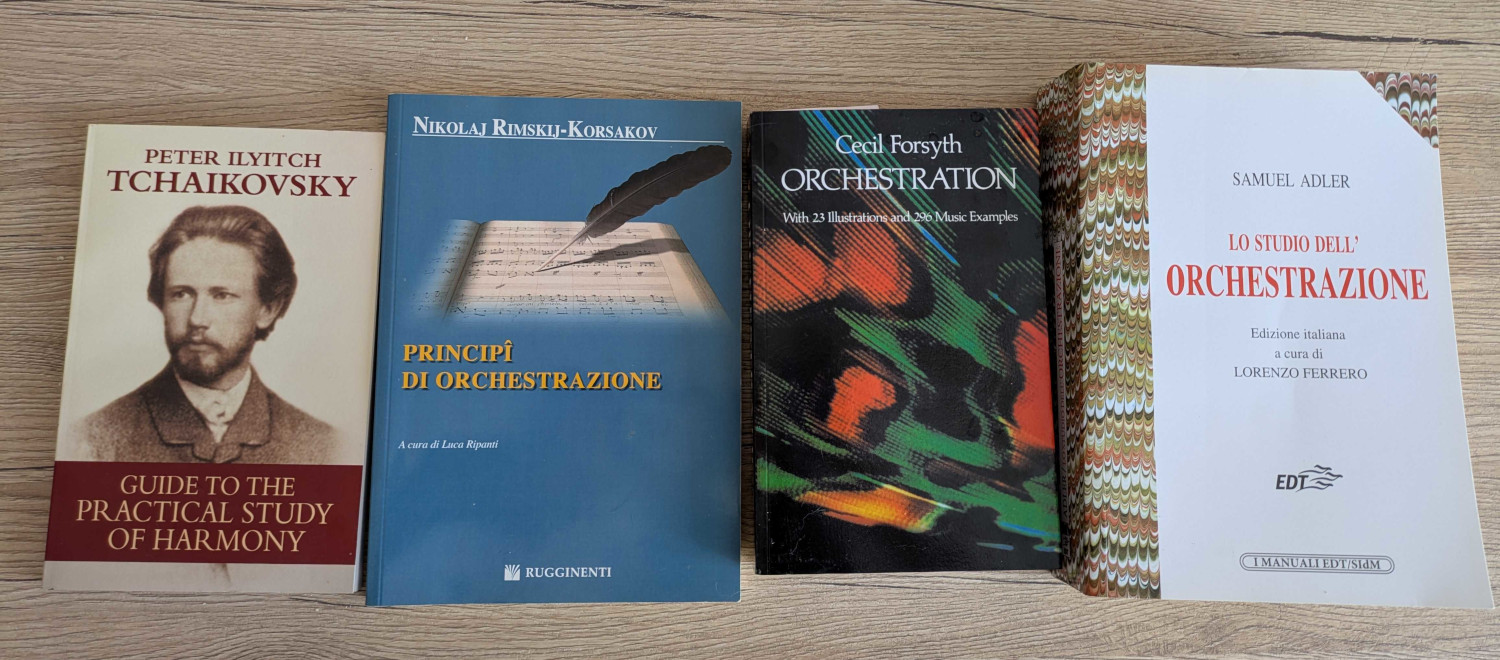

That doesn’t mean you need to study in full detail the books listed below…

I mean, I did buy all of those for my own personal leisure, but I haven’t read them all either, and probably never will read them all. I did read Rimsky-Korsakov’s “Principles of Orchestration”, though, and I did read Adler’s book on orchestration too, and I’m glad I did. Neither require you to have a deep, or even good, knowledge of music theory (which Tchakovsky’s book does, instead), but both do an excellent job at helping you understand what an orchestra is: introducing the different sections, the different instruments, and what they can bring to the table.

It’s not really important, for virtual orchestration, to know that an excessive use of percussions can completely drown your other instruments because of just how loud they are in real life (a common mistake composition students make, apparently), as you’re always in full control of the mix, and you can make anything sound as loud or quiet as you want it to sound. But it can be very important to know more about the different textures instruments have, which instruments are often played together to convey what vibe or feeling, how instruments can double each other in unison or at different octaves, and so on and so forth. By reading Rimsky-Korsakov’s book and listening to some of my favourite tracks, for instance, I’ve learned that, for some reason, a flute and a bassoon playing the same notes at different octaves (due to their different ranges) gives a very winter-y feel, and that tremolo strings have the same effect. At the same time, that’s how I learned that flutes doubling what 1st violins do makes strings sound stronger and “fuller”: and the moment you realize that, you’ll start to also realize that, for instance, that’s what John Williams does a lot in his own soundtracks. Just knowing these little things can make a huge difference, because again: maybe your flutes or violins sounds are not amazing, on their own, but together you don’t really need to hear either, it’s their combination that matters the most, and helps getting a more realistic sound.

If you don’t feel like reading anything (even though Rimsky-Korsakov’s and Adler’s books are really interesting and easy to breeze through), there are a ton of videos, e.g., on YouTube, where you can learn pretty much the same things with actual examples, especially in terms of which textures work well with others, which don’t, or techniques you can use like doubling at the octaves.

But enough chit-chat, let’s talk of more practical stuff…

The journey begins!

When I first started dipping my toes in virtual orchestration, at the time, I had just started to learn about JACK, and loved the endless possibilities. By searching around, I found a free book called Linux Midi Orchestration, by amateur musician and open source aficionado Peter Schaffer. It’s a long and detailed description of the process Peter followed to achieve what he wanted, by basically leveraging JACK’s potentiality to the fullest, using different software for different requirements in his workflows.

While I was truly inspired by his huge efforts, I felt the approach to be a little to complex for me to replicate (especially since I was new to JACK myself), and so I started trying to move step after step on my own instead.

The first thing I looked at, at the time, was Lilypond, for a simple reason: it was pretty much the de-facto standard for beautiful rendering of classical music scores, and so it seemed to make the most sense for orchestral music. If you’re not familiar with it, Lilypond is basically to music sheets what LaTeX is to typesetting: using a set of programmatic instructions, you can define how a score will look like, which instruments should be included, what notes to add and so on. Besides, it can be configured to output MIDI files as well, which is what I’d need to then have something I could play out and sequence. Long story short, that didn’t last long… I really love Lilypond (I still use it a lot whenever I need to quickly write down some music ideas that come to mind), but IMHO it’s simply not suited for virtual orchestration: it’s excellent as a tool to render beautiful scores you can print, but it’s not user friendly enough for writing music you want to virtually orchestrate, for the simple reason that it’s not what it was meant to do.

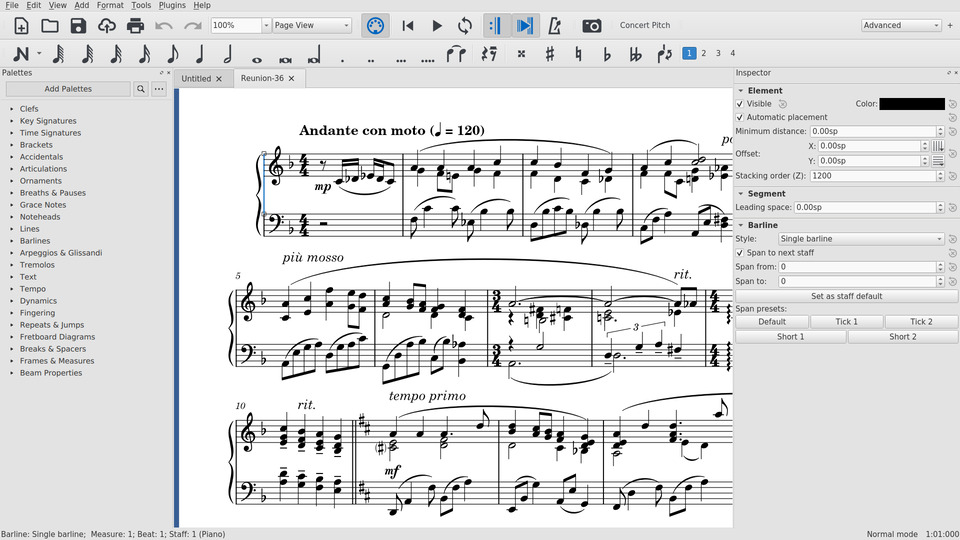

I quickly ended up using what so many others (Peter Schaffer included) have been using for the task, that is MuseScore. The reason for that was quite simple: MuseScore aims at providing what Lilypond does too, creating beautiful scores, but does so with a WYSIWYG user interface, and with many settings related to the playback aspects of it (e.g., how to render the resulting MIDI in real-time). There’s basically no better software for the job in the open source world (at least when it comes to orchestral and classical music), and it could be argued that it has slowly started to take over some well established proprietary solutions as well (like the previously mentioned Sibelius or Finale).

Now, it’s important to point out that I ended up choosing MuseScore because I like to actually write the score for the parts. I’m not a huge expert of music notation: I can’t really read it, for instance, or at least definitely not fast enough (it would take me some time just to identify the right notes). But, after studying a bit of music in middle school, I’ve always found it much easier to write using music notation, than using stuff like piano rolls for instance. Maybe it’s because music is not that different from math, and so writing parts feels more natural to me that way, than drawing bars on a piano roll. But YMMV, of course: what works for me may not work for you, and that’s not really important, since this is just the scoring part, and we’re not to the relevant part yet.

Long story short, I now had access to an excellent tool for quickly scoring orchestral parts that I could easily iterate over, but there was an important problem left. While MuseScore’s audio rendering of the various instruments was serviceable, it was definitely not good enough. It used (and uses) a decent enough soundfont, and instruments kinda sound like how they should (meaning you can recognize them), but it’s not very realistic. This is indeed where virtual orchestration gets in, so let’s check what were the options.

Getting some better orchestra sounds

There are a ton of good libraries out there. There are some excellent libraries too. There also are a lot of very expensive libraries, though. And good chances are that, if you’re an accomplished music composer, regularly writing music for TV shows or movies, you bought a license for more than one of them.

This is not what this blog post is about, though, and neither was it what I was interested into. I wanted to figure out what options were available in the FOSS space, and to my surprise, there actually were a lot of them, in different formats. A few of those options, in no particular order, are the following:

The “BBC Symphony Orchestra Discover” library is one that many end up using, since it’s the free version of a more comprehensive and complete library by Spitfire Audio, who’s a known actor in the virtual instruments space. I actually like Spitfire Audio a lot, since they have a LABS section that includes a ton of experimental, and completely free, VSTs for different sounds, that I’ve used a lot in my compositions. That said, being VSTs, they’re meant to only be usable on Windows or macOS: and while there are ways to get Windows VSTs to work on Linux too (e.g., using LinVst), they’re not really efficient when you have to use a ton of them at the same time, and a whole orchestra definitely falls in that space.

A much more Linux-friendly format is SFZ, which is a plain text format that can provide instrument data for sample instruments, meaning it can instruct a compliant sequencer on how to play existing samples (e.g., recordings of actual violins) depending on incoming MIDI instructions. It has a rich syntax that can cover many different scenarios, meaning that it’s relatively easy to aggregate multiple samples to have them work together for the purpose of simulating a specific instruments. Being a well known standard format, it’s been adopted by many in the FOSS world, which is why libraries like Sonatina, the Versilian orchestra or Virtual Playing Orchestra all chose it as the format for their own virtual instrumentation.

And then there’s Muse Sounds, which was made by the same people that brought us MuseScore, and is basically a library of MuseScore plugins for realistic playback of different instruments. Some of those plugins are free, some aren’t, but the orchestral ones are, to my knowledge, all freely available, and provide realistic orchestral sounds to replace the default soundfont we mentioned previously. Being made specifically for MuseScore, they also obviously have a good integration in MuseScore itself, thus being able to provide high quality orchestra sounds to scores written there. And the quality is indeed high, as confirmed by some sample videos you can find online, like this one. At this point you may wonder: Lorenzo, you’re already using MuseScore, so obviously you went for that? And well, it may sound like the obvious choice, but there are a few reasons (some possibly controversial) that convinced me to actually stay away from that, and go for something else instead.

First of all, while orchestral sounds are indeed free, you can only install them by going through MuseHub, which is basically MuseScore’s marketplace. So far, nothing necessarily bad: it’s what other players in that space do too, Spitfire Audio included (that’s how you install their LABS VSTs, for instance). The main problem with that is that MuseHub is a proprietary application, which is already weird when you take into account that MuseScore is open source instead. Not only that: when you install MuseHub, for some weird and unknown reason it requires root access to be launched. Now, I don’t know about you, but that’s a big “hell no” in my book: I’m most definitely not going to give a proprietary tool that I don’t know anything about root access, especially when there’s no reason at all for that to be needed (plugins are saved in the user’s folders). Now, that may have changed in the meanwhile, but that was definitely still true when I tried it last year, and that was enough for me to steer away.

Even if that weren’t an issue, though, there’s another reason I’ve stayed away from Muse Sounds. Being a new feature, it was only added in MuseScore 4, the new version of the software. That’s reasonable, but the problem with that is that, while MuseScore 4 has been released a couple of years ago already, not everyone is very happy with it, mostly because it doesn’t seem very stable yet, and most importantly it apparently still lacks features compared to MuseScore 3. I did give it a try some time ago, and to be honest I didn’t like it very much: while part of that may be the different UI I simply wasn’t used to, it wasn’t indeed very stable (it crashed more than once), and I noticed some other changes to my existing scores that I didn’t appreciate. As such, I decided to stick to MuseScore 3 instead (even though Fedora made that harder by only keeping MuseScore 4 in the repos), which for my limited needs was and is more than adequate.

So what did I end up using instead?

Virtual Playing Orchestra it is!

Out of all the SFZ-based libraries I mentioned in the previous section, I ended up choosing Virtual Playing Orchestra (or VPO, for short). The main reason for that was that it’s basically a collage of all the best samples (from the author’s perspective) from different resources, including Sonatina and Versilian. Besides those, in fact, it borrows samples from other free libraries like No Budget Orchestra, the one made available by the University of Iowa, and Philarmonia Orchestra.

Most importantly, I particularly like how VPO provides a ton of different SFZ scripts for different instruments in different sections. You’ll find instruments divided in sections as we introduced them initially (woodwinds, brass, percussions, vocal, strings), and then there are different scripts for when you need solo instruments vs. an instrument section (e.g., a single flute vs. a flute section), by using different audio samples. Considering each instrument may sound differently depending on the articulation that’s used to play them, there are different scripts for different articulations too: a pizzicato violin section sounds very different from a violin section playing tremolo, for instance, which means entirely different audio samples are often used even if the instruments are exactly the same. At the same time, there are also scripts that leverage different ways to dynamically switch articulation (and so samples) on the fly, as part of the same SFZ script: VPO itself, for instance, uses keyswitching for the purpose, meaning you can use some specific notes outside of the range of the specific instrument to change articulation on the fly, without you needing to instruct the sequencer to use a different SFZ script for the purpose. This gives the library a ton of flexibility: besides, by relying on a plain text and open format like SFZ, it also means that it can be extended and/or improved, by possibly using the same samples it provides in slightly different ways (as I did in part; more on that later). Another interesting feature that it has is Dynamic Cross Faded (DFX) support for brass instruments, which basically allows for, and I quote, “blending of low and high velocity brass samples based on the position of the mod wheel with the purpose of achieving a more realistic sound for long held notes”. This is an optional feature but it does sound really cool, especially when you think about how brass instruments really sound like.

Of course, it comes with a few shortcomings. It doesn’t have a piano as part of its instruments, for instance, but admittedly that’s not really a big deal: there are a ton of alternatives for when you need piano sounds as well as part of your orchestra (e.g., the Salamander Grand Piano SFZ, that I’ve used myself more than once). I have a bit more of an issue with some of the samples, which may not always sound great: I don’t like its clarinets, for instance (their attack is always too slow, even when you use automation to reduce it to the minimum), which means that, whenever clarinets need to take a more prominent role (something I can’t hide with other sections, for instance), I tend to rely on samples from different libraries for that.

Another interesting aspect that I found out is related to strings. In VPO, they’re obviously split in different subsections (1st violins, 2nd violins, violas, cello and basses). Some of the samples, like tremolo, staccato and pizzicato, sound really great in my opinion: “regular” strings not as much, though, as I’ve always felt they sound a bit thin. What I discovered, though, is that they can sound much more lush if you don’t leave them on their own, but add another layer of strings from a completely different library (e.g., KBH Ultima Strings), with proper mixing to avoid strings sounding too loud because of the doubling. If you think about it, a violins section sounds like it does because there’s a dozen or more individual violins playing together, and it’s a sound that’s very different from the one a single violin produces. As such, by adding another library to the mix, you’re simply adding more variety to the section, as if you were adding even more violins to the mix. Again, little tricks and a bit of misdirection, but you’d be surprised by how much they can help under some circumstances!

A VPO template for the Ardour DAW

Now, I’ve talked about MuseScore for scoring, and VPO for getting better orchestral sounds: how can we put the two together?

MuseScore 3 does support SFZ out of the box (one of the features that’s not available in MuseScore 4 anymore, for some reason), but loading VPO in MuseScore itself is not something I was particularly interested in. In fact, while it may help for getting more realistic sounds in MuseScore, it also makes MuseScore much heavier, which complicates the scoring process: and as I mentioned, MuseScore default sounds are not that bad, and are more than enough to get a preview of how “good” the score is coming out. Besides, it makes the whole process of mixing much more awkward as well. In fact, no matter what kind of music I’m working on, I do all my mixing and mastering in a DAW called Ardour, and so being able to handle all the actual orchestration in Ardour instead would have been much better, especially if I could work on different sections, or even instruments, separately from a mixing perspective.

Luckily for me, fellow musician and developer Michael Willis created an Ardour template specifically conceived for VPO, that I found to be an astonishing starting point. Michael, in fact, prepared a template that had different tracks for different instruments and articulations, all panned according to where they’d be in an actual orchestra seating, and with three different reverbs (using Dragonfly Reverb, an excellent plugin written by Michael himself) for spatially positioning different sections from back to front. The end result was something that tried to replicate the seating diagram below.

To render the VPO SFZ files, he leveraged the sfizz plugin, a very lightweight implementation of the format that makes it easier on the CPU to load many instances of different instruments.

Considering my requirements, I ended up tweaking the template a bit according to my own needs. Specifically:

- Rather than having a single track per instrument, I chose to only have one track per grouped instrument (e.g., a single “flutes” track instead of two “flute” tracks). This helped reduce the number of sfizz instances even more.

- I switched to some slightly customized versions of the “Standard” VPO SFZ files, rather than the “Performance” ones Michael used by default.

- I collapsed all articulation tracks into one, as I wanted a single track to be able to dynamically change articulation using custom SFZ scripts and proper automation (more on that later). This also helped reduce the overall number of sfizz instances.

- I added more tracks that I use regularly (e.g., piano, guitars, bass, drums, vocals, etc.) as I wanted the same template to be usable both for plain orchestral music, and for rock+orchestral music: depending on the actual requirements, it was easier to remove tracks I knew I wouldn’t need, than adding some that were missing.

- I added some basic EQ to all tracks to try and prevent some mudding in the mix, in order to avoid too many frequencies in the same place due to the number of tracks in the template.

This meant now I had all I needed: MuseScore to write the parts, VPO to play them and an Ardour template to actually use VPO and the score in an organized way. How does it look like from a bird’s view?

The complete workflow

As I mentioned a few times, the way I use it MuseScore is fine for scoring, but that’s not where I want to render the actual orchestration. I want to handle mixing and mastering of everything (orchestra, band, etc.) in Ardour, where I have more control over the whole process. This means Ardour is where the actual virtual orchestration (MIDI-to-audio) happens, in my case, via VPO, and where mixing and mastering of everything happens as well, which makes it possible to more seamlessly blend instruments coming from different sources (e.g., the scored orchestra and rock elements).

In a nutshell, this means that we can summarize my workflow as a multi-step process. I initially documented this in response to a comment on an Ardour Discourse post where I introduced some of my music, and it’s basically the following:

- First of all, I score all the parts in MuseScore: using MuseScore’s default sounds, I can get a good preview of the balance of the different parts.

- Once I’m relatively happy with the result (I may get back to MuseScore later on), I export all the parts to separate MIDI tracks: this means I’ll have a MIDI file for flutes, one for bassoons, one for french horns, one for 1st violins, etc.

- I create a new Ardour project using my customized VPO template.

- I import each MIDI track to the right orchestra instrument (flutes MIDI track to the “Flutes” track in Ardour, etc.).

- Considering I’m using a single track per instrument, in any case I need an articulation change I use automation in Ardour to trigger it, using custom CC messages that are defined in my custom SFZ scripts (more on that in a minute).

- I write/import/record all the other parts, if needed (e.g., if this is an orchestral rock track, this means scoring drums, recording bass and guitars, possibly adding synths, etc.).

- Once everything is there, I work on the mix, which can take a very long time considering the amount of tracks: orchestral mixing in particular needs a lot of work, as the balancing I did in MuseScore may be different when switching to the VPO sounds, and then the orchestra must have the right balance with rock instruments as well, if present.

This is it, basically: maaybe not really straightforward or easy, but definitely not that complex either. It’s mostly just time consuming, depending on how many articulation changes need to be automated, or on how much work is needed on balancing the different tracks in the mix.

Articulation changes deserve a few words, as I mentioned more than once that I did customize the VPO SFZ scripts a bit for the purpose. These customised scripts can be found on this repo, and are basicaly variants of the VPO keyswitching scripts, where rather than relying on “unreachable” notes to switch articulations (that would have forced me to add those unreachable notes in the MuseScore score, making them too “ugly” and awkward should I want to share the score), I instead rely on a custom MIDI CC (14), where depending on the range the MIDI CC value is in, I trigger an articulation change rather than another. A MIDI CC in the 40-59 range, for instance, means using the “regular” samples, while the 20-39 range implies tremolo, 0-19 sustain and so on.

Initially I tried to automate these articulation changes by adding MIDI actions to the MuseScore project file itself, but that soon proved to be a frail approach, especially since adding custom MIDI actions to MuseScore (something I’d need for my custom CC) requires a manual editing of the score file, and any attempt to do that programmatically resulted in a broken score file. Considering that Ardour supports MIDI automation, it then seemed easier to just trigger articulation changes once I imported MIDI tracks there, by manually adding the required MIDI CC messages to the automation of each track that needed it. That would be enough for the VPO SFZ script, via sfizz, to react to it by changing samples dynamically. An example from a track I composed recently can be seen below.

This is part of the automation for the “1st Violins” track, where over the course of a few seconds, articulation changes a few times. We can see the MIDI CC 14 value going from 24 (meaning we were playing tremolo strings up to that point, since it’s in the 20-39 range) to 85 (staccato strings, 80-99 range), then after a while changing to 50 (regular strings, 40-59 range) and finally down to 21 (tremolo strings again). Since I’m working in ranges, the automation is configured to use discrete steps, otherwise Ardour would create smooth transitions in between those numbers, which would cause articulation changes to happen at the wrong times, and even the wrong articulation to be used at times (e.g., if you go from 85 to 21 linearly, you pass through the 60-79 and 40-59 ranges first, which is not what we want).

Long story short: a bit cumbersome to add manually, but it does work beautifully!

There’s another little trick that can be seen in that screenshot. As you can see, the track I’m working on (1st Violins) is muted there, and below you can glance another one with a similar name (1st Violins (audio)). That’s because, although I start from MIDI tracks because that’s what I import from MuseScore and then render via sfizz, I serialize all of them to corresponding audio tracks for mixing. The reason for that is simple: there are a lot of MIDI tracks, and a lot of sfizz instances, which despite my optimizations (e.g., collapsing some instruments and articulations together) is still a bit too much for my laptop to handle in real-time when there’s a lot going on, which is particularly a problem when I also need to record something live (e.g., a guitar part) while the orchestra plays in the background. As such, any time I’m happy with how a specific track sounds, I simply have an audio track record the output of the associated MIDI track, and then disable that one and the associated sfizz instance. As a result, Ardour ends up with many already processed audio tracks, which are easier to handle for recording/mixing/mastering purposes. Of course, that does mean that, if it turns out I need to change something in that instrument part, I need to go back to editing the MIDI track and re-serialize it to audio, but that’s an acceptable trade-off when it comes down to getting a responsive UI to work with that won’t boil down my computer!

What about some music?

But enough talk. What about talking about some actual music instead? To put my money where the mouth is, basically…

I think that a good example to start from is one of my symphonic poems, Lost Horizon, as that’s an entirely orchestral track, with nothing else to “hide” it. It’s also one of the first times I used this workflow extensively. As such, it highlights what can be considered the strenghts and weaknesses in my workflow, and possibly in the libraries I chose to use (if not in my arrangement skills themselves). Assuming the SoundCloud embed works as expected, you should be able to play it below.

What will be immediately apparent is that things sound much better and more realistic when there are more things happening (smoke and mirrors, misdirection), or when instruments with better samples are played, and less so in other cases. For instance, I’m not a huge fan of how the more somber french horns sound in the intro, but it gets better when woodwinds get in at about 30 seconds. The same could be said for the strings section starting at about 1:12, which gets better when tremolo strings break in at 1:35, simply because tremolo strings samples are much better in VPO. I do like the sounds of the celesta (about 2:30) and harp (about 2:55), and that falls down to the realism that arrangement can give: using those instruments the “right” way can give a special vibe to your track, even when the other samples are less believable. The whole tapestry sounds better, again, when there are more things happening, like at 8:40 or 9:09 where you have multiple sections playing together, and louder. The part that starts at 10:15, instead, is an example of how doubling at the octaves and then adding more textures on the way can make everything sound “bigger” and more lush: no one will believe it is a “real” orchestra, but at least it sounds close enough for a little bit.

But as I mentioned initially, if on its own the orchestra can feel a bit “naked” at times, it does help when it takes more of an accompaniment than a prominent role, e.g., in a more rock oriented track where its purpose is to provide the right “bang” or level of pompousness (which is what I like in a song!). A good example of that is a track I wrote for fun a few years ago, called All I want for Christmas is Odin, in which I basically tried to convert Mariah Carey’s “All I want for Christmas is you” in a more evil and menacing viking/symphonic metal track.

If you skip the dumb intro in the video, at about 1:15 the track starts with a full orchestral setup. In this case it sounds more believable than the symphonic poem as I focused specifically on some sections (and I improved my arrangement skills a bit). Then, at about 2:00, rock instruments join the orchestra, and it all sounds bigger. For a while, you only have rock instruments on, until at about 3:00 the orchestra joins the other instruments again, which with the help of the choir does sound huge. The same can be said for when the orchestra joins the rock instruments again for the bridge, at about 4:00, making it sound more ominous, or for the solo a few seconds later. The end result is that the orchestra sounds more “believable” than it did in “Lost Horizon” for the simple fact that it’s not on its own, and there’s more stuff it can bounce off to.

All of this “works” mainly thanks to Michael’s excellent VPO Ardour template, with the few tweaks I made to it: since all instruments are in the same project, and they’re all spatially placed the same way (using panning and sharing the same Dragonfly Reverb instances), they all blend together better, as if they really were taking the same space, and make each other stronger and more rooted as a consequence.

Another interesting example (bear with me, we’re almost done!) is how I used the orchestra in The Case of Charles Dexter Ward.

This track, like the previous one, is a metal track with orchestra, but using a different approach: the first half of the song is almost entirely orchestral (in particular starting at about 1:20), with clean/acoustic guitars playing an arpeggio and some atmospheric samples; the remainder of the song just has rock instruments, except for the very end where the orchestra comes in again. The atmospheric intro is where the orchestral instruments can shine more, since they can sit a bit back and still play an important role, and in fact I’m pretty happy with how it came out. The same can be said for the ending, which has a slower metal part, atmospheric samples again, and the orchestra playing a callback to the arpeggio in the intro: again, this way the orchestra helps make the song sound more “bombastic”, without a need to necessarily sound too believable as an orchestra itself.

One last example (it’s the last one, I swear!) is a part of a 27 minutes symphonic rock track I published a few months ago, called Cleopatra, in particular the “The Power of Rome” subsection.

This track helps understand better how the orchestral samples can sound both on their own, and with rock instruments. In fact, in this short track the same part is played twice, in sequence: the first time the orchestra plays alone, and the second time, after a short metal break, orchestra and rock instruments play together. It’s an easy way to figure out how, despite our virtual orchestra on its own is not that bad (or at least, I like how it came out), it can sometimes feel a bit “hollow”, while once it joins the rock instruments everything sounds much more “massive”.

Feedback welcome!

I’m well aware my approach may look a bit convoluted, and probably inefficient, by some. I’m also aware that my orchestral music may not sound as impressive to others as it feels to me, but I wanted to share my process nevertheless, in case it could help others interested in getting something similar out by just using FOSS. I’m definitely interested in any kind of feedback or suggestion you may have on that (or on the music I created that way), so if you have any, please do feel free to reach out on Mastodon or Bluesky!